July 8, 2021

Coalville, UT to Salt Lake City, UT

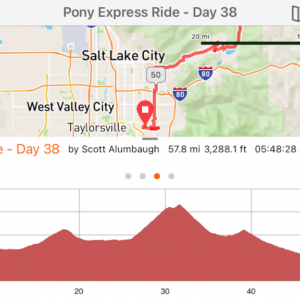

57.9 miles/3,288 feet

upper 90s/winds 10-15+

https://ridewithgps.com/trips/70822220

The last day of my ride started warm and clear. As I was checking out of the hotel a man stopped me to ask about my trip and to tell me about his son who was riding his bike from New York to Florida on some trail. He seemed appropriately worried, but comforted knowing his son would never be in too remote of an area. Which once again made me silently apologize to MJ.

I rode over Interstate 80, back through Coalville, then northwest toward the little town of Henefer on a rail-to-trail path that ran along Echo Reservoir. As a former railroad track, the trail had a steady grade, in this case slightly downhill. It was nice not to have to ride the undulations of the road, and not to be riding next to cars.

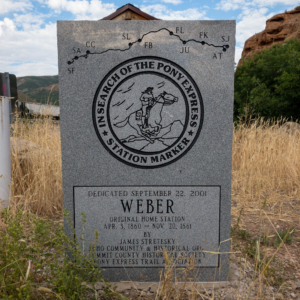

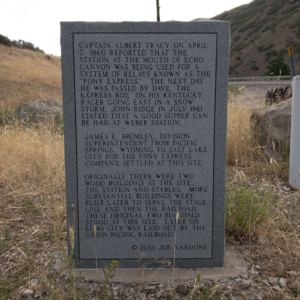

Between Coalville and Henefer is Echo, a town at the head of Echo Canyon. A monument for the Weber Pony Express Station sits just east of town, at the intersection of Echo Canyon and the Weber River. From this point, the Pony Express Bikepacking Trail rejoins the Hastings Cutoff/Donner-Reed/Mormon Trail and follows it the rest of the way into Salt Lake City.

The Weber River, which is dammed here to create Echo Reservoir, runs from southeast to northwest along this stretch. The river creates a T-intersection for Echo Canyon which starts here and runs northeast toward Evanston, WY. Interstate 80 (which runs through Echo Canyon) makes a ninety-degree turn at the town of Echo to the southeast to go through the Wasatch Mountains via Parley’s Canyon, thence into Salt Lake City. You can look down Echo Canyon from here, and even with an interstate running through it you get a sampling of the red rocks of Echo Canyon and some idea of its natural beauty.

There is not much in the town of Echo. I took a couple of quasi-Highway 66 photos and moved on. As I pedaled along a frontage road between Echo and Henefer, I noticed a blinking sign on the freeway: Highway 65 Closed. Highway 65 was my route through the mountains. What if I went there and it was closed? How else could I get through? I thought about the irony of getting so close to my destination only to be stopped here, just fifty miles away, but kept riding anyway thinking I might find some way around. It turned out that the highway was open; the bridge to it over the freeway was being rebuilt was all, so there was no direct freeway access. Crisis avoided.

Henefer was a tidy little town with, reportedly, an ice cream parlor (not open yet) and a couple of monuments. It was my last stop on the Weber River. Highway 65 crosses the river and runs south-southwest from there, over three passes, to Salt Lake City via Emigration Canyon.

The highway was narrow, but well-paved, lightly traveled this time of the morning, and had a gentle rise. Until it didn’t. Once it started to lift toward the first pass, the going got slow. The sun was hidden probably half the the time behind morning clouds, but when it came out it felt every bit as strong as you might expect for a mid-90-degree forecast. Winds were very light. It wasn’t long before my shirt was soaked.

Let me clarify: the back of my shirt, under my hydration pack, is perpetually wet, pretty much all day every day. This morning, with this climb and under these conditions, the entire shirt was wet.

Occasionally the sun would hide for a while, a puff of wind might blow across my bow, and I would get a little respite of coolness. All in all it wasn’t a bad ride. Just slow.

Eventually I reached the top of the first rise, called Hogback Summit. Apparently, it was nicknamed Heartbreak Ridge because the Mormon emigrants reached this point only after a long, hard pull (to which I can attest), only to get a good view of the much taller mountains they still needed to climb.

From there the road descended into East Canyon, which follows along the East Canyon Creek. The creek is dammed here, creating a nice reservoir. When I rode past there were kayakers and paddle boarders playing on the lake.The air was so still I could hear their voices from quite a way across the water. This was a nice flat stretch, a good place to rest up before the biggest climb of the day.

Irene Paden describes the emigrants’ journey through this section:

Beyond [Henefer Creek’s] headwaters, the great wagons rolled and thundered through Pratt’s Pass [Hogback Summit] on the summit of a low divide. Down another steep hill the wagons pitched while all hands and the cook held back on ropes and on the wheels; along the bed of the tiny streamlet, crossing and crisscrossing it for two or three miles down to East Canyon with its steep watercourse known variously as Canyon, East Canyon, or Kenyon Creek. Here they really learned the meaning of ‘trouble.’

Small shallow East Canyon Creek had to be forded ten or more times; the trail was crooked beyond reason and thick with amputated willow stubs, testimony to the herculean task accomplished by the Reed-Donner party in forcing a passage through mountains at this point in 1846. The Mormons, traveling in their footsteps a year later, accomplished the thirty-five mile trek from Weber River [Henefer] to Salt Lake Valley in three days; but they recorded that it took the Donner party sixteen days of hard labor to win through the valley. For years the cut willow stubs remained, and the animals baptized them with blood from torn hoofs and gashed legs.

Irene D. Paden, The Wake of the Prairie Schooner, p. 295-296

The climb up to Big Mountain started just a little past the south end of East Canyon Reservoir. At the base of the climb, Jan’s route splits off to take mountain bike trails up to and over Big Mountain. Her route note for this section starts with the words, “Hike-a-Bike, Mormon Trail Overgrown,” which translates to “You have to get off the bike and push it through bushes.” That was as far as I had to read before I decided there was no way I was going to take the mountain bike route. I stuck on 65. That was hard enough.

If this section didn’t have quite so much climbing, and if it weren’t at the end of a five-week ride, I might consider riding the dirt sections for fun. You know, as a day trip from Salt Lake City, maybe with a shuttle to the top. By sticking to the highway I bypassed a few Pony Express station sites that are only accessible off the dirt trail. Part of me is sorry I missed them. But the part of me that was riding the bike that day did not. I was hot and tired and was ready for the ride to end. I was, as they say, smelling the barn and trying my best to speed toward it.

I don’t know how far the climb was up Big Mountain or what elevation gain or how steep the average slope was. I can only tell you that it was a long, slow, difficult climb. I was in first gear most of the way, which amounts to about four to five mph. It was yet another section where there was nothing to to but keep my legs spinning. Occasionally, for a break, I would shift up a few gears, stand, and treat the the bike like a Stairmaster. When that became tiresome, I’d sit, quickly drop the bike back into first, and go back to spinning. The best way to make a climb like this is to sit up to get more air in your lungs and to take advantage of the slow speed to look at the surrounding scenery. But even with the scenery, it was, well . . . not tortuous, not like trying to fight a Wyoming headwind . . . but let’s say, very taxing.

My mantra at times like this is a haiku by Issa that people who have read my other ride accounts probably know by heart from reading it so often:

O snail

Climb Mount Fuji

But slowly, slowly

They’ve read this poem often because I have never been a good climber. Even back when I was probably in my best shape I’d get dusted. My friend Darell Dickey would whiz past me, and just to be a jerk, sit up from the handlebars and pump his arms as if he were running, big smile on his face. My ungrateful son, Kazu, will practice one-handed wheelies on the mountain bike I bought for him while I’m spinning in first gear, gasping for air, tongue hanging out like a water-starved dog. It’s embarrassing how slow I can be.

But there you have it. I crawled up the north side of Big Mountain slowly, slowly, until at last I made the pass. There is a parking area up there with pit toilets and some historical markers. There is also a view down through the canyons to the south and into the Salt Lake Valley. The Wasatch Mountains are steep-sided, precipitous, and the view over the lower peaks and down the canyons is spectacular.

Here is Richard Burton’s description of the view in 1860:

Big Mountain lies eighteen miles from the city. The top is a narrow crest, suddenly forming an acute based upon an obtuse angle. From that eyrie, 8000 feet above sea level, the weary pilgrim first sights his shrine, the object of his long wanderings, hardships, and perils, the Happy Valley of the Great Salt Lake. The western horizon, when visible, is bounded by a broken wall of light blue mountain, the Oquirrh, whose northernmost bluff buttresses the southern end of the lake, and whose eastern flank sinks in steps and terraces into a river basin, yellow with the sunlit golden corn, and somewhat pink with its carpeting of heath-like moss.

Richard Burton, The City of the Saints, p. 190-191

Do you need to ride a bike up Big Mountain to appreciate the view. No. My suggestion is to drive. But speaking of bikes and cars and riding and driving, the closer I got to the city, the more cyclists there were; not travelers, like me, but folks out for some hill-climbing and exercise. You know, fun. Cars passed by more frequently, too, in both directions. Not all moved over as far as I would have liked. But the highway was narrow, and the sight lines often short. I couldn’t really hold it against anyone to keep to their lane, even if it meant driving closer than I would prefer.

The descent down the north slope of Big Mountain was a white-knuckle ride. Some years ago I descended a hill like this in the Eastern Sierra Nevada Mountains (Janesville Grade) with another rider on the Gold Rush Randonnee. When we got to the bottom he said, “I need a cigarette.” It was that kind of descent

I don’t get quite the same satisfaction out of steep descents. I was glad I had oversized disc brakes and rotors because I made good use of them here. The road was still narrow, so I held to the middle of the lane until I heard my radar beep. Without it, I would never have known cars were behind me for the whistle of the wind in my ears. Eventually the road flattened out into an area known as Mountain Dell. Dell Creek is dammed here to create two more reservoirs, Little Dell and Mountain Dell. Irene Paden again:

A mile and a half down, and down [from Big Mountain]. No animals were left on on the wagons but the faithful wheelers remaining to hold up the tongues. Every available man held back on a rope. By ’49 the timber had been cut for the building of Salt Lake City and the caravans twisted here and there between the jagged stumps down to a small, sheltered hollow known as Mountain Dell. It was a lovely meadow, but miry. The wagons often celebrated their return to the horizontal by stalling in the mud with promptness and precision, and the tired travelers, admitting that they were sunk, gave it up for the day, camped, and fought mosquitoes.

Irene D. Paden, The Wake of the Prairie Schooner, p. 295-296

If nothing else, paved Highway 65 at least wasn’t miry or mosquito-ridden. I was nearing Salt Lake City, but from Mountain Dell, I still had one final climb: Little Mountain. Yep. Not particularly long, not particularly steep. But it had to be done, and after the climb up Big Mountain I rode up the hill more slowly than I might have otherwise. Eventually, though, there I was, looking down at the reservoirs, looking forward to a long descent down Emigration Canyon to my destination, Salt Lake City.

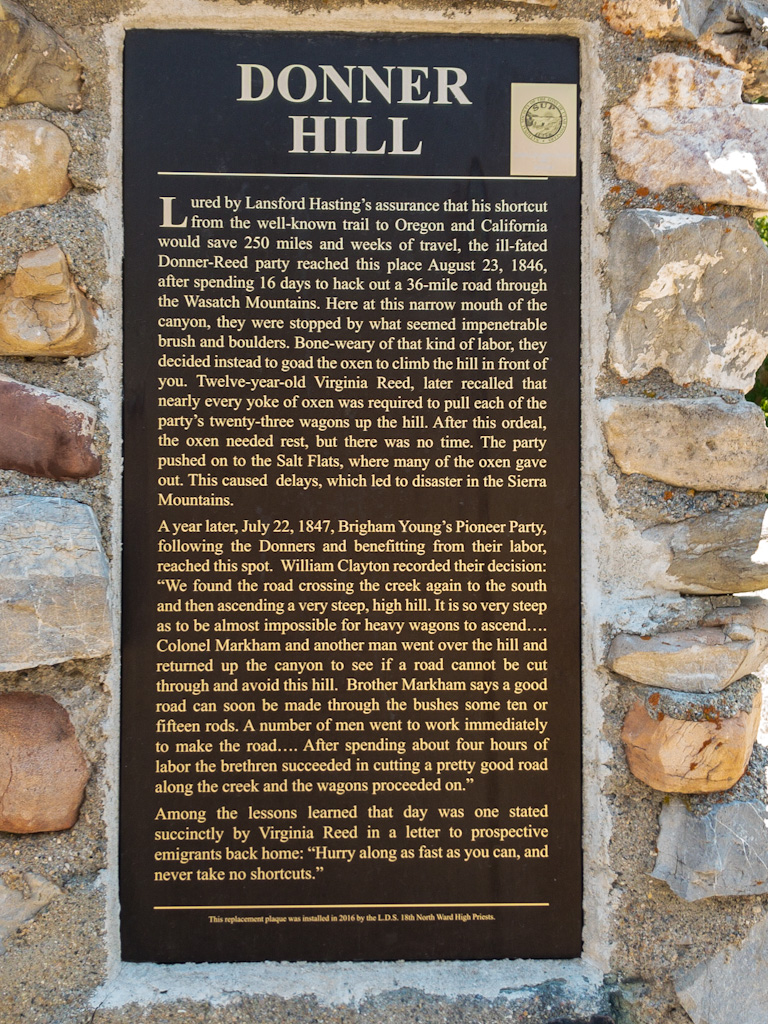

Another white-knuckle ride down the winding canyon. There weren’t too many cars or bikes, so the ride never felt sketchy that way. It actually transitioned into a long, pleasant descent, not as steep as the others, and more tree-shaded. More houses along the way, more cars parked on the side, and with them the potential to be doored. But I descended without incident, stopping to take pictures at monuments to the Donner-Reed Party and the Mormons that popped up here and there. In a way it was kind of a big finish, this slalom ride down historic Emigrant Canyon into the City of the Saints.

Soon enough I was in the thick of it, and saints or no, it was just like riding in any other city. Four lanes of traffic all rushing from one red light to the next. Watching out for cars turning in front of me, or speeding up to pass and turn right. I had mapped out a bicycle-friendly route, but sometimes that meant no more than a nominal bike lane alongside that rush.

I sped past the This Is The Place shrine, and decided I didn’t need a dose of Mormon mythology just then. My destination was in the suburbs south of downtown, so eventually I turned left. Happily, south was downhill and downwind, so I had an easy time of it, unless you take into account the bus driver who kept passing me only to stop at his stop, then pull out again to cut me off rather than have to pass me again. I was relieved when he finally turned off after a couple of miles of this cat-and-mouse.

I made it to a cafe I had marked on the map just a short distance from Connie and Mike’s house, thinking I’d rest and recuperate, that is, recruit, for a while before invading their home. But the place turned out only to be a drive-thru, no seating area. Quick search. A promising place called 3 Cups a mile or so away. Up a hill, naturally. But once I arrived, worth the ride. Nice spot in the shade out front by my bike to drink an Americano and a gluten-free cinnamon roll.

Feeling . . . well . . . recruited, I guess, I remounted the bike and rolled downhill. Connie was home and I (rudely) stopped her from hugging me and explained about all the sweating I had done earlier and all of all the grit I had no doubt picked up since. One shower later we were sitting and talking and waiting for Mike to get back home from work.

It was lovely in a way I don’t know whether Connie and Mike can understand. I don’t know whether I can really convey to them how much it meant. To ride so far . . . To be in the care of Samaritans along the way . . . To be on your own for such long stretches of time . . . To be in such remote places . . . And then to be in the hands of family, relatives by marriage who welcome you and treat you as blood. It is a comfort and a blessing beyond my ability to describe.

I have now been here three days, and will be here one more. After that, I’ll catch the train, which will deliver me to within two miles of my home in Davisville, where (I hope) Lisa and Kazu will pick me up and help get all my luggage home. It feels strange to realize a trip I had planned for a year is nearly over. But all things considered, I think it has gone on long enough.

I can’t thank you enough for posting this. Not only was it a great read but it has inspired me in the following ways: 1. I will go West to East. 2. I will not stick to the exact route 3. I will skip the section between St Joseph and Casper.

I’m glad you enjoyed the read, but it sounds like I did the opposite of inspiring you. If anything I wrote keeps you from riding the route east of Casper, I apologize.

Fantastic writing and amazing perseverance! It was fabulous to go on this trip with you! Thanks for including me. (lily)

Thanks for coming along!

CONGRATS! Thanks for posting so we could follow along your adventures. Welcome home!!! Wish I could be there to cook you a big celebratory feast! –Meera

Oh, that would be wonderful! Thank you so much for following along.

Congratulations, Scott. You’re an inspiration.

I don’t think I’ve ever been called that before. Thank you!

P.S. That was from me — forgot.to sign it. —babz

Thx for letting me know!

It always takes me a while to reenter my own reality after reading one of your posts, Scott. You had me the entire way. Thanks for a unique armchair adventure. Enjoy the train ride—moving without having to make it happen. And welcome home.

Thanks for the kind words Barbara. There were days on the ride when I looked so forward to being on the train: no decisions, someone else at the wheel. I only wish it were a longer train ride.

?? Congratulations Scott on a job very well done. both your writing and your riding were Pulitzer quality. Great history and Samaritans along the way. I was with you in spirit. Now you’re probably ready for your first E bike.

Welcome home!

Thank you Barry. Ebikes are looking really good right now. If only you could recharge them in the desert.

Wow! Congratulations, Scott. What an incredible adventure.

Margaret

Thanks Margaret!

It was worth the wait… to become famous at the very end.

Cheers Scott, well done.

Thanks! I thought of you at a number of times on this trip, but this seemed like the appropriate place to write you in.

And my mom told me that being a screw-off would never pay.

Ha! I laugh last!

We can’t wait to see you! Thanks to Connie and Mike and the rest of the family. Big hug to Rick for setting up the bike that got the Nut through this journey.

The Nut? Really?

Well done bro! Now time to rest up and dream about the next adventure. Yay.

Thanks Dana. And thanks for all your support.

Woo hoo!! Great finish to a fantastic journey and journey report. The only thing missing is a picture of the writer.

Hmmm. Maybe I need to add one.