June 21, 2021

Torrington, WY to Guernsey, WY

49.5 miles/1,530 feet

low-60s/mild headwind

https://ridewithgps.com/trips/69733456

Fair warning: I’ve got nothing interesting to say about my ride today. This will probably be the most boring entry I’ve posted so far, at least as far as the travelogue part is concerned. Maybe I can add in some good history and background to make it worth your time.

[I am having internet-slowness issues, so please forgive an excessive number of typos. It’s too painful to proof anymore.]

I started off in Torrington, WY, itself a pretty boring town. The coffee at the hotel I stayed in was watery. Not weak, watery. So I started in the opposite direction of the Pony Express Trail and rode into downtown, which was as empty as it had been the day before when everything was closed. It was Monday morning; shops were open for business. But still dead.

I got an Americano and ordered a breakfast burrito to go from Java Jar, which shares a pretty nice space with the Tourist Info Center, in case you ever make it to Torrington and want some of that. Tourist info, I mean. Or espresso, I guess. Anyway, I sipped coffee and wrote a postcard to Lisa and Kazu then sent it off and got rolling by 8:30.

For the first time since leaving St. Joe, it was actually cool. High 50s or low-60s, maybe. It stayed cool most of the day, with fair-weather cumulus hanging overhead like giant mushrooms. It was also a little breezy (what else is new?), and on my nose (no surprise there) but not as bad as I had feared.

South of Torrington I looked for a monument for the Cold Springs Pony Express Station, one of at least two Cold Springs stations I know of (the other being in Nevada). I found Cold Springs Avenue, and the Cold Springs Business Park, and a monument to the Oregon Trail. But alas, no Cold Springs Station.

A good deal of today’s route was on pavement, so I made decent time all the way to the Ft. Laramie Historical Site. Here is a long-ish, but tidy history of the fort:

Recorded history of the section immediately west of Scott’s Bluff begins about the year 1818 when Jaques La Ramie, a French Canadian, built a trapper’s cabin near the junction of the North Platte and the Laramie River. He was trapping in the vicinity of Laramie Mountains when the erection of the tiny dwelling established him as the first permanent resident of the section. Four years later the Indians clinched his claim to permanence by leaving his bones to bleach on the headwaters of the river that bears his name. . . .

[In 1834, Robert Campbell and William Sublette stopped to trade at the Laramie River on their way to the rendezvous at Green River.] At Laramie River, the trading was excellent. Sublette left Campbell to hold down the situation and hurried on. Campbell, getting help, built a small trading post consisting of a high stockade of pickets and a few tiny huts inside. . . . he named the place Fort William, after his partner; but in two years, it evolved into what history knows as Old Fort Laramie. . . .

In 1835 . . . Fort William passed into the hands [of the American Fur Company] and was rechristened Fort John after John B. Sarpy, an officer in the company. . . In 1836 the American Fur Company deserted the the stockade of Fort John and built a better one a few hundred yards up Laramie River on a small plateau. The name went with it but ‘Fort John on the Laramie’ was soon corrupted to the simple ‘Fort Laramie’ that has remained in use ever since. It was of adobe, copying those forts farther south that had been built with Mexican labor. . . .

By the year 1845 the fur traders dealt mostly in buffalo robes, beaver having passed gradually from its position of importance, and although the other forts did a brisk business, the preeminence and prestige of Fort Laramie was unquestioned. [Francis] Parkman wrote of the American Fur Company at Fort Laramie that they, ‘well-nigh monopolize the Indian trade of this whole region. Here the officials rule with an absolute sway; the arm of the United States has little force; for when we were there, the extreme outposts of her troops were about seven hundred miles to the eastward.’ . . .

The lack of governmental protection mentioned by Parkman was felt so keenly that in the summer of ’49 the United States purchased Fort Laramie and garrisoned it for the avowed purpose of giving advice, protection, and the opportunity of buying supplies to the emigrants. It had a monthly mail service, and the marching thousands moved perceptibly faster the last few miles, hoping for a letter from home. Comparatively few were received, for they were apt to be longer en route that the would-be recipients; but the myriads of letters sent eastward fared better, and, if the addressee stayed long enough in one place, they arrived in the fullness of time.

As I mentioned before, Fort Laramie was the first permanent settlement the emigrants had seen de since Fort Kearny, way back at the transition of the prairie to the high plains. Once past Fort Laramie, they (and now I), left the plains behind and started the climb up to the Rockies.

Fort Laramie marked the end of the High Plains, the beginning of the long upgrade haul to the Rocky Mountains. It was the end of the line for the sick, the tired, the downhearted. Tempers, frayed by weeks of mud, dust, sunglare, and Indian alarms, snapped. . . .

Fort Laramie was about an even one-third of the 2,000 mile distance from St. Joe to Sacramento—665 miles according to J.H.Clark, and during the 37 days it took him to travel this he tabulated also 248 graves and 35 abandoned wagons. . . .

While California gold was (hopefully) at the end of the continental rainbow, it could only be reached step by painful step, and Fort Laramie was the most important mile-stone to date. If you made it to Fort Laramie you were already entitled to spit in the Elephant’s eye; to reach Laramie was like crossing the equator on an ocean voyage. Accordingly, you approached the fabled spot with some ceremony.”

Merrill J. Mattes, The Great Platte River Road, p. 492, 502, 504

To read the diaries of the Gold Rush, one might suppose that elephants flourished [on the Plains] in 1849, but the emigrants weren’t talking about wooly mammoths or genuine circus-type elephants. The were talking about one particular elephant, the Elephant, an imaginary beast of fearsome dimensions which, according to Niles Searls, was ‘but another name for going to California.’ But it was more than that. It was the popular symbol of the Great Adventure, all the wonder and the glory and the shivering thrill of the plunge into the ocean of the prairie and plains, and the brave assault upon mountains and deserts that were gigantic barriers to California gold. It was the poetic imagry of all the deadly perils that threatened a westering emigrant.

Merrill J. Mattes, The Great Platte River Road, p. 61

The landscape has certainly changed. There are still miles of crops, more miles of range land, more feed lots, but the terrain is rougher, rockier. The sky, if possible, is even bigger. All day I tried to capture some aspect of the scenery, but a camera lens is just too narrow.

Since yesterday I’ve been keeping an eye out to the west looking for Laramie Peak, a 10,000 ft mountain that dominates the area around it, as well as the emigrant diaries. I saw it not long before riding into the town of Fort Laramie. And while Laramie Peak is tall, it just made me realize that it’s the first mountain I’ve seen on this trip. I’ve seen hills—hillocks, Ms. Paden likes to call them—and have had more climbs than I care to count. But no actual mountains. In California, are you ever out of site of some piece of land that rises noticeably? Even in Davisville, the heart of the Central Valley, we have the Vaca Hills to the west and Sierra Nevada to the east.

It is typical of Californians to compare everything to California. Or Disneyland (“That interchange is just like the Autopia”). We have everything—ocean, rivers, mountains, desert, etc.—and every natural feature everywhere else can me measured and judged by that standard. I remember, for instance, when my mom took her first horseback riding trip to Spain she came back saying it looked just like Calabasas (a town at the west end of the San Fernando Valley). On a trip to Greece, sitting in an outdoor restaurant watching the sunset over a bay on Ios, one of the crew on my boat was unimpressed. She saw the sun set over the ocean every night from her cliff-side condo in Capitola. What was the big deal?

That’s a little extreme, I think, and overly obnoxious. The point I’m trying to make is that once I noted Laramie Peak, it was there as a landmark, but not as a particularly impressive one. In fact, past Fort Laramie, I pretty much stopped taking landscape pictures at all because everything is starting to look familiar. The striated rocks, the yuccas, even the open ranges, and yes, even the wide, wide sky. Because even though the North Platte runs deep and swift through this area, everything looks and carries that dry feeling of California in summer, all of the colors are less saturated than they were further east and lower down.

After the Fort Laramie Historical site I had a slow passage over gravel roads and steep hills to get to my destination in Guernsey. At one point there was a turn-off to see an emigrant’s grave, but the hill was steeper than I wanted to tackle so late in the day’s ride. Further west, a small area called the Bedlam Ruts appeared just a little off the road, so I took that side-trip. It is an area marked by wagon ruts, mostly visible as a depression winding through the surrounding land. Not much to see, but as it is so off the beaten path, so to speak, I thought it worth the trip.

Along the way I ran into cattle gauntlets, areas where cattle out on the range were ranged across the road. For some reason, they seemed to gather at the cattle guards, those rows of steel pipes laid across the road. I know cattle aren’t particularly aggressive, but they are large. They would stare at me as I passed, and only at the last second, move out of the way.

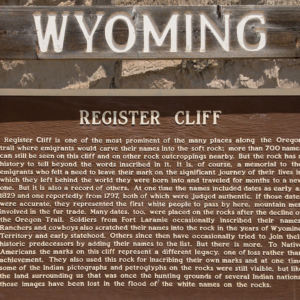

Closer to town, I came to two well-known areas. The first was Register Cliff, where emigrants and fur trappers and others carved their names. I swear emigrants in the mid-1800s carved their names into anything that didn’t move. At Register Cliff, so many emigrants left their mark that they wiped out the petroglyphs that had been inscribed earlier. More recent taggers in turn—many in this century—have done the same to the emigrant’s carvings. If I had more patience, I might have searched for the oldest carvings. As it was, I noted the landmark and moved on.

I came next to the Guernsey Ruts area. At this spot, the wagons actually wore through rock. Of all the areas purporting to be the Oregon Trail, this is the most dramatic so far. I believe I can take this one as authentic. Which is not to say the others aren’t. Only that this one is the most patent example of the permanent environmental impact of so many wagons over a stretch of land.

On the road from there to town, I passed another emigrant grave, this one of Lucinda Rollins. Apparently she was 24 when she died near there in 1849. The grave I passed earlier was for Mary Holmsley. (I have a book put out by the Oregon-California Trails Association that has details on the marked emigrant graves. Not that that’s much help to me right now.)

These women’s graves bring to mind a point I’ve wanted to raise before but didn’t seem to have the right place to say it, which is this: No wife on record made the decision to emigrate; it was always the husband, and often over his wife’s objection.

It is interesting to look at the decision to emigrate to Oregon or California in the light of the legal model of husbands’ power. In their diaries and recollections many women discussed the way in which the decision to move was made. Not one wife initiated the idea; it was always the husband. Less than a quarter of the women writers recorded agreeing with their restless husbands; most of them accepted it as a husband-made decision to which they could only acquiesce. But nearly a third wrote of their objections and how they moved only reluctantly.

John Mack Faragher, Women & Men on the Overland Trail, p. 163

On a similar note, while we’re on the subject of women finding themselves, and even dying, in an environment not of their choosing, I thought I’d share these thoughts on women who did not emigrate all the way to the Pacific, but instead settled in the Plains:

The Great Plains in the early period was strictly a man’s country—more of a man’s country than any other portion of the frontier. Men loved the Plains, or at least those who stayed there did. There was zest to the life, adventure in the air, freedom from restraint; men developed a hardihood which made them insensible to the hardships and lack of refinements.

But what of the women? Most of the evidence, such as it is, reveals that the Plains repelled the women as they attracted the men. There was too much of the unknown, too few of the things they loved. If we could get at the truth we should doubtless find that many a family was stopped on the edge of the timber by women who refused to go farther. A student relates that his family migrated from the East to Missouri with a view of going farther into the West, and that when the women caught sight of the Plains they refused to go farther, and the family turned south and settled in the edge of the timbered country, where the children still reside. That family is significant.

Literature is filled with women’s fear and distrust of the Plains. It is all expressed in Beret Hansa’s pathetic exclamation, “Why, there isn’t even a thing that one can hide behind!” No privacy, no friendly tree—nothing but earth, sky, grass, and wind. The loneliness which women endured on the Great Plains must have been such as to crush the soul, provided one did not meet the isolation with an adventurous spirit. The woman who said that she could always tell by sunup whether she should have company during the day is an example. If in the early morning she could detect a cloud of dust, she knew that visitors were coming! Exaggeration, no doubt, but suggestive.

The early conditions on the Plains precluded the little luxuries that women love and that are so necessary to them. Imagine a sensitive woman set down on an arid plain to live in a dugout or a pole pen with a dirt floor, without furniture, music, or pictures, with the bare necessities of life! No trees or shrubbery or flowers, little water, plenty of sand and high wind. The wind alone drove some to the verge of insanity and caused others to migrate in time to avert the tragedy. The few women in the cattle kingdom led a lonely life, but one that was not without its compensations. The women were few; and every man was a self-appointed protector of women who participated in the adventures of the men and escaped much of the drabness and misery of farm life. The life of the farm woman was intolerable, unutterably lonely. If one may judge by fiction, one must conclude that the Plains exerted a peculiarly appalling effect on women. Does this fiction reflect a truth or is it merely the imagining of the authors? One who has lived on the Plains, especially in the pioneer period, must realize that there is much truth in the fiction. The wind, the sand, the drought, the unmitigated sun, and the boundless expanse of a horizon on which danced fantastic images conjured up by the mirages, seemed to overwhelm the women with a sense of desolation, insecurity, and futility, which they did not feel when surrounded with hills and green trees.

Walter Prescott Webb, The Great Plains, p. 505-506

From Lucinda Rollins’s gravesite I rolled into town and found The Bunkhouse Motel, dropped my things off, got a pint of Ben & Jerry’s and some other possibles at the local market, then ate, showered, and took a lovely hour-long nap. I’ve since had dinner and am now wrapping up for the night. I’m planning a long ride tomorrow, and the weather is threatening to heat up again.

Happy June Birthday, Scott! Finally posting to see if my name comes through. All those other witty/intelligent posts with Anonymous on them. Probably from me.

No doubt

You’ve amassed a whole herd of elephants, Scott. Hannibal had nothing on you. Roll on. —Babz

Dear Scott a.k.a. The nut,

HAPPY BIRTHDAY!

Want you to know that we’re enjoying your blog and are very glad that you’re the one doing the riding and writing and we’re doing the reading. Stay well ! Stay safe !

D7J

Glad you’re enjoying the blog. Thank you for reading! And thanks for the birthday wishes. I think I will plan to spend the days on the bike.

Love ending my day reading of your adventures. I am reading about John Jacob Astor and the American Fur Company . Perhaps your next bike trip should be the Lewis and Clark Trail. Lolo Pass to Astoria. Had a great historian on board for my recent trip from Clarkston, WA to Astoria. Charlene

Charlene, let me make it through this one first!

On a drive back from the dinosaur museum in Thermopolis, Wyoming, probably about 20010, my family saw the ruts in the rock and I was impressed that these grooves in the stone were cut without intension in only a few decades. Your navigating cows now, but you may soon need to facedown bison. I remembered some blocking the road and backing up till they got out of the way.

No bison so far, but we’ll see …

I love the town sign. Not as weird as the Mitchell sign (tiger in flames), but makes me wonder if I’d be sorehead. You’re entitled to spit in the Elephant’s eye now. Glad you’re getting closer to home.

For a guy who got Nothin you sure wrote a whole lot of somethin! Enjoyed it

I’m glad!

FYI-I keep showing up as “Anonymous” But that was me, Laughing Dog.

Stu

Somehow I knew that. But still, thx for clarifying.