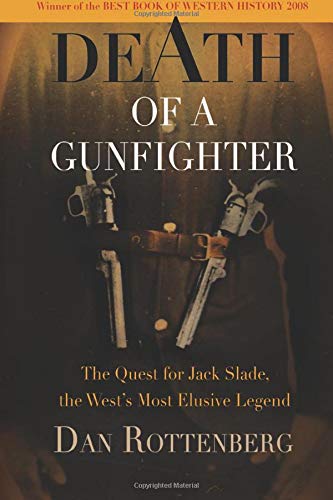

Dan Rottenberg, Death of a Gunfighter: The Quest for Jack Slade, the West’s Most Elusive Legend (Westholme 2008)

This book represents the author’s quest to sort the fact from the fiction about Jack Slade, one of the best known characters associated with the Pony Express. To paraphrase from the book’s blurb . . .

This book represents the author’s quest to sort the fact from the fiction about Jack Slade, one of the best known characters associated with the Pony Express. To paraphrase from the book’s blurb . . .

Joseph Alfred “Jack” Slade was division supervisor over the roughest portion of the route, and was tasked with making it safe. He captured bandits and horse thieves and drove away gangs, and shot to death a disruptive employee. He became known as “The Law West of Kearny.” Slade’s legend grew when he was shot multiple times and left for dead, only to survive and eventually exact revenge on his would-be killer. But once Slade had restored the peace, leaving him without challenges, his life descended into an alcoholic nightmare, transforming him from a courageous leader, charming gentleman, and devoted husband into a vicious, quick-triggered ruffian—a purported outlaw —who finally lost his life at the hands of vigilantes. Since Slade’s death in 1864, myths and stories have defied the efforts of writers and historians, including Mark Twain, to capture the real Jack Slade. Despite his notoriety, the pieces of Slade’s fascinating life have remained scattered and hidden . . .

Apart from the sensationalistic blurb, I found this to be the most satisfying and rewarding book related to the Pony Express I’ve read so far. It is thoroughly researched, the writing excellent; but even more, the author’s passion for the material breathes life into the book. I really got a sense that the author enjoyed writing every page, and that joy somehow transcends the writing, elevates it. The only other nonfiction author I’ve read who comes across the same way is Wallace Stegner, who seems incapable of writing a boring sentence. Stegner is a very high standard, and I don’t know if Rottenberg’s books all compare. But this one did. Rottenberg states in the Preface that he has had a lifelong ambition to write about Jack Slade. It’s probably the number of years that account for the depth of the book.

The book also excels in laying out the various versions of key events in Slade’s life, from which the author chooses a version to argue is the most plausible; but more importantly, he does not force the reader to accept his conclusion, but rather, just lays out the stories and facts he’s been able to collect. It’s a nice contrast from most of the books I’ve read so far, which state their version as fact with no additional information for the reader. For instance, the Settles give this account of Slade’s revenge on Old Jules Beni, the man who shot Slade and left him for dead:

” . . . Slade, having recovered from his wounds, determined to make an end of the affair. Riding up and down the line he soon located the outlaw hangout. Collecting a party of dependable men, he made a surprise attack in which Old Jules was so badly wounded he could not escape. Slade tied him to a corral post, cut off his ears nailed them to a the fence as a warning to others. When he had done this he fired bullet after bullet into the helpless old villain’s body. One of the ears remained there for weeks, it is said, while Slade took the other to wear upon his vest as a watch charm.”

Settle and Settle, Empire on Wheels, p. 46

In Death of a Gunfighter, Rottenberg details the extent to which Slade sought to avoid a subsequent confrontation with Old Jules. Jules had fled after shooting Slade, and Slade vowed not to pursue Jules so long as he stayed away from Slade’s jurisdiction on the stage line. Eventually, Jules did wander back and boasted he would kill Slade if they ever met. Slade apparently felt his authority would be undermined by Jules behavior and his boasting. But before going after Jules, Slade first went to the Army at Fort Laramie, the only federal government in the area, to ask permission to go after Jules. In the end, it seems Slade himself did not shoot Old Jules, as a couple of his crew had found Jules first. In short, Rottenberg’s version lacks the lurid flourish of the Settles’ version. As a result, the reader gets a more complex version of the events and of Slade.

Probably the most poignant part of the book is Slade’s hanging by a vigilante mob in Montana just a few years later. Slade apparently had something of a Jekyll and Hyde nature: a gentleman when sober, an absolute demon when drunk. He fell into a habit of going on benders and making a lot of trouble in Virginia City. Eventually, the local vigilante committee hung him for it. Rottenberg, while not defending Slade’s behavior, makes a strong case that however disruptive Slade may have been, he did not commit a capital crime. That while he deserved punishment in the form of jail time or banishment, for example, he did not deserve to be hung.

I could go on about different aspects of the book and how well they are treated. Rather, I’ll just leave it as I started: I found this book a very satisfying, rewarding read.