July 3, 2021

Farson, WY to Granger, WY

52.4 miles/1,360 ft

low 90s/winds west to 15

https://ridewithgps.com/trips/70548781

I got an early start the next morning. I wanted to make Granger, about 55 miles away, and I knew the second half of the ride would be on dirt. I just didn’t know what kind of dirt, and after the ride I had the day before, I didn’t want to get a late start and find out it would be all bad.

For the same reason, I deviated from Jan’s route out of Farson. Her route sticks to the off-road emigrant trail just west of a perfectly good highway. I wanted some early miles under my belt, so I stuck to the pavement.

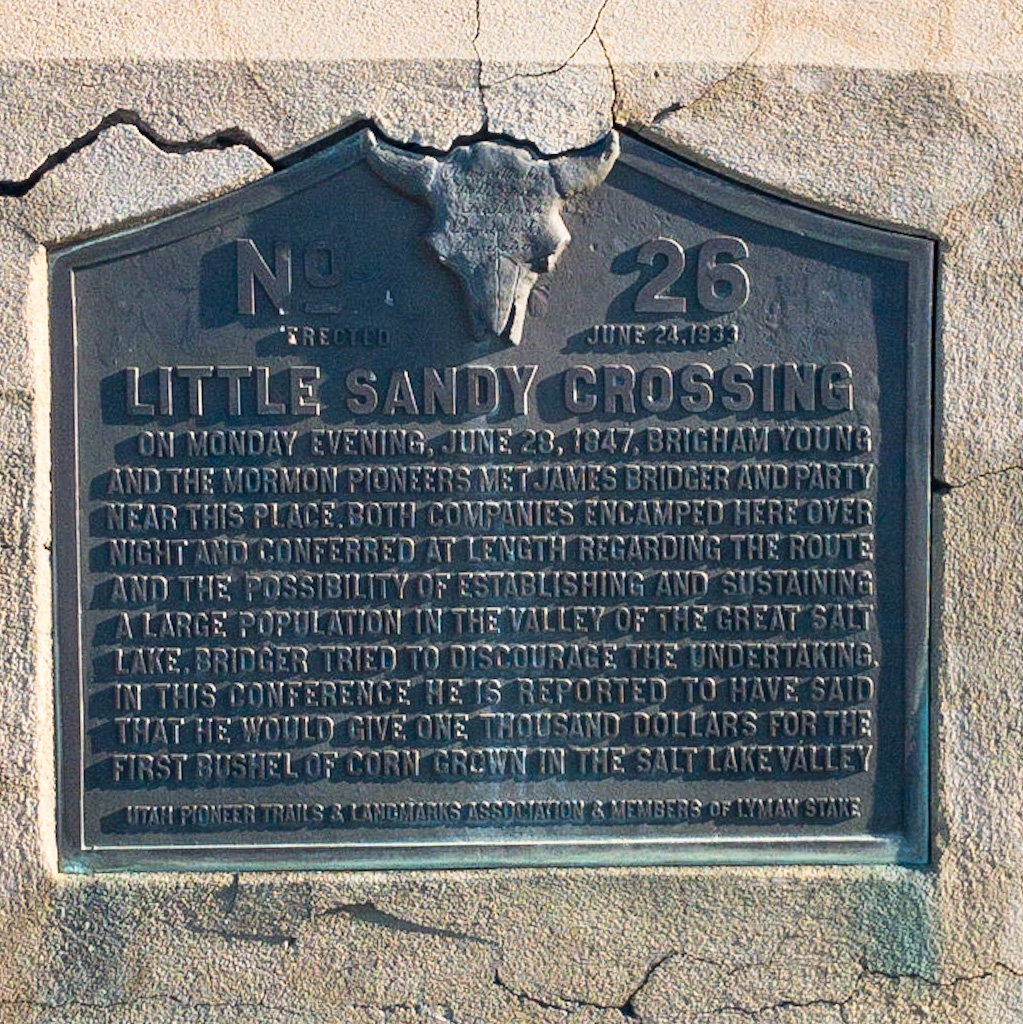

One benefit of that was to come across a monument. In 1847, on the Little Sandy River near near the future site of Farson, the mountain man Jim Bridger met with Brigham Young, who was leading the first contingent of Latter-Day Saints to the Salt Lake Valley. It’s said that Bridger told Young it would be a fine place to settle, though he made some crack about how you’d never be able to grow corn there for the frost.

This meeting is also indicative of another aspect of the Mormon migration. There is a spot I will pass on the way into Salt Lake City. Tradition has it that Brigham Young, on seeing the Salt Lake Valley for the first time at this spot proclaimed, “This is the right place; drive on.” The spot is called This Is The Place Heritage Park. The tale suggests a tone of divine revelation in Young’s proclamation. In reality, Young and his counselors had assiduously studied the entire western part of the continent for well over a year prior to leaving before deciding on the Great Salt Lake Valley.

Mormon legend has it that when, on July 24, 1847, Brigham Young, weak with mountain fever, came jolting in a white-top over the last summit in the road down Emigration Canyon and gazed over the sagebrush flat toward the Dead Sea, he spoke with the power of revelation and said “This is the place.” Brigham, however, held it irreligious to call upon the Lord until you had first exhausted your own resources. Long before that day he had determined on Great Salt Lake Valley. He had, in fact, decided on that general vicinity sometime in 1845.

Throughout 1845 the destination of the Saints was constantly discussed by the leaders who would have to manage the emigration, and they made the most minute study of the available literature. It is not clear that Fremont’s second report was decisive. They used it with exceeding care to rough out an itinerary, but they could get little more from his account of the Great Salt Lake country than that the lake did not have the mysterious whirlpool which legend attributed to it, that its islands were barren, and that the canyons which ran down to it from the east were well timbered. It seems likely that Young knew more details about Zion by the end of 1845 than Frémont had observed there. Certainly he knew much more by the end of 1846.

It is clear that Young had decided on the Great Basin, rather than Oregon or coastal California, by midsummer of 1845. It was an inevitable decision: there was, in fact, nowhere else to go. Israel could survive only if left to itself long enough for Young to organize and develop its institutions. That meant that it must find a place where the migrating Americans would not be tempted to settle. That, in turn, meant the Great Basin. But also, as Young seems to have understood quite clearly, Israel must be near enough the course of empire to sustain itself by trading with the migration. And that meant the northern portion of the Great Basin. It meant, in fact, one of no more than three places, Bear River Valley, Cache Valley, and Great Salt Lake Valley. All three places seem to have been in his mind in ’45, and there are still references to Bear River Valley late in the autumn of ’46, but the actual choice proved to be between the other two. Later we shall see the choice being made.

The meeting between Bridger and Young here, near the future Home of the Big Scoop, was part of the intelligence gathering that went into the final decision.

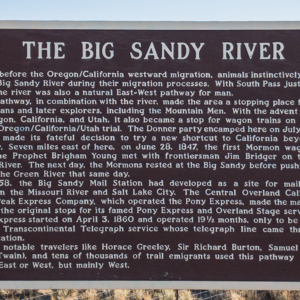

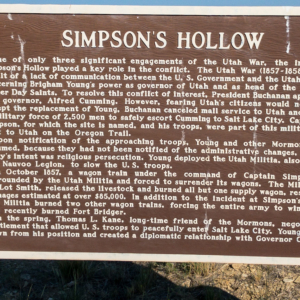

The highway was virtually empty, the wind light. I had to stop and remove my right pedal to oil it: going through so much water had caused an irritating squeak. Pedal reattached, I made good time down the little highway. By and by I came to yet another place I had been anticipating: Simpson’s Hollow. It was here that, effectively, the Mormons won a war with the United States without firing a shot.

A little background (bearing in mind that this is a very broad-stroke, thumbnail history of a very complex period of US history).

Mormons had been run out every town they had settled in since Joseph Smith had his first religious epiphany in 1820 and published his Book of Mormon in 1830. They first gathered in Kirkland, Ohio, near Independence, Missouri. But the Mormons had a tendency to vote as a block, and not to be above selling that block to whichever side would guarantee them the most religious freedom. They made enemies among Missourians (aka “Pukes,” by which term De Voto refers to Missourians throughout his book). Among them, Missouri Governor Lillburn Boggs, who issued an extermination order, tantamount to declaring open season on Mormons:

It was Lillburn W. Boggs who, as governor of the state, had loosed six thousand militia on the Mormons when, in 1838, Carroll and Davies Counties flared with precisely the same mob violence we have seen at Nauvoo [Illinois]. The Gentiles were howling that the Mormons must be expelled, the Mormons howling that the Lord had loosed His people to vengeance. There were night riding, burnings, floggings, lonely murder, and occasional attacks in force. Finally Governor Boggs directed the general of his militia, “The Mormons must be treated as enemies and must be exterminated or driven from the State if necessary for the public peace — their outrages are beyond description.” That was the “Extermination Order” of October, ’38, and the Mormons have not forgotten it to this day, quite rightly.

Bernard De Voto, The Year of Decision, 1846, p. 85-86

Nauvoo, Illinois, is where the Mormons went next. Eventually the Illini wanted them expelled, by force if necessary. In June 1844, Joseph Smith and his brother, Hyrum Smith, were jailed in Carthage, Illinois. A mob stormed the jail and killed both men. This is when the process of looking for a permanent home became a necessity. In order to gather and make final preparations, the Mormons created settlements on both sides of the Missouri River just above the mouth of the Platte River in the winter of 1846. (Aside from community building, this necessitated a treaty with the Native Americans on the west side of the Missouri on whose land the Mormons built their temporary city, aka Winter Quarters. Young’s negotiations with the locals and the US Indian Agent is a separate, entirely fascinating subject.)

When Brigham Young led the vanguard out to Utah in 1847, none other than Lilliburn “Extermination Order” Boggs was emigrating to California as well. And just as the Mormons feared violence at the hands of emigrating Pukes, other emigrants, fed on stories of Mormon vengeance, feared violence from them as well. One way to avoid the conflict and still move wast was for the Mormons to keep to the north bank of the Platte River, separated by all that water from everyone else who came up from the south and kept to the south bank. The Mormons had to cross the North Platte no later than Fort Laramie and travel at least to South Pass along with everyone else, but so far as I’ve been able to determine, no religion-based violence ever broke out. In later years, as the trail became too crowded and the forage and water scarce south of the Platte, more emigrants took to the north bank, known by then as the Mormon Trail.

Knowing this background, it’s easy to understand that when the Mormons set up shop in the Great Salt Lake Valley, they were particularly security conscious. They established colonies at all of the passes into the Great Basin: San Bernardino, for instance (by Cajon Pass) and Mormon Station (Genoa, Nevada, at the base of the passes into South Lake Tahoe).

A twist in the plot arose to complicate Brigham Young’s plan of a Zion in the desert: When he decided on Utah as the new home for the Mormons, it was Mexican territory. He planned to use the Texas method of settlement:

Because the majority of the Mormon population was Anglo-American, there were many aspects of Mormonism’s Manifest Destiny that aligned with the traditional American ideology. Taking whatever land they saw fit was certainly one of those, though the Mormons were neither as aggressive nor martial about doing so in comparison to many of their contemporaries. In many respects, they planned to follow the ‘Texas method’ of land acquisition, wherein they would dominate a certain area by sheer numbers in order to gain political power, and then exert their influence once they were strong enough to declare independence. Being the ‘first’ to occupy, cultivate, and improve the land the Mormons to establish a territory of their own where they would be the majority and none could expel them.”

Natalie Brooke Coffman, “The Mormon Battalion’s Manifest Destiny: Expansion and Identity during the Mexican-American War” (2015). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses., pp.69-70

But by the time the Saints arrived in Utah, the US had fought Mexico and had obtained ownership to the land. The Mormons found themselves once again under US jurisdiction. When Utah became a territory (in 1850), President Buchanan wisely named Brigham Young as governor. But the US sent in officials, including a federal judge and others, who rubbed the Mormons the wrong way.

One basic cause of the difficulties [between Mormons and Gentiles] during [the 1850s], and indeed in later years, was the existence of a public opinion extremely hostile to the Mormons and prepared to seize upon any pretext, whether valid or not, to renew the attack upon the Church. . . .

A second cause of trouble between the Mormons in Utah and the Government was the selection of inferior men to fill the Territory’s offices. . . .

Another irritant, of lesser importance than some mentioned here, was the question of land ownership. . . Before the Saints could claim the land as their own . . . certain procedures established by Congress had to be followed, among them disposal of Indian rights and a survey of the area. . . .

For their part, the Mormon’s characteristics and activities were as conductive to strife as the temper and policies of their opponents. . . . After their experiences with inflamed Gentile mobs, the Mormons were quick to look for new attacks in Utah, an attitude that times became unjustified truculence. Furthermore, their continual insistence upon the superiority of their faith under divine sanction proved most objectionable to other Christians. . . .

Norman F. Furniss, The Mormon Conflict, 1850-1859, p. 11-14

The net result was a lot of bad blood until, in 1857, the federal appointees, claiming fear of losing their lives, fled Utah. Buchanan sent in troops, ostensibly to establish new feds in the territory, resulting in the Mormon War, or the Mormon Conflict. Two results of that altercation are germane here.

First, as I said at the beginning of this diversion, the Mormons essentially wiped out any potential threat the Army could pose by the simple act of depriving them of provisions, which they did, in part, at Simpson’s Hollow:

On October 4 a small band of Mounted Mormons led by Major Lot Smith bypassed the Tenth Infantry and fell upon two of [Russell, Majors & Waddell’s supply] trains camped along the Green River, a very few miles from Colonel Waite’s command [Fifth Infantry]. Secure in the knowledge that the army’s calvary, the Dragoons, was some 700 miles to the east [as it had been ordered to assist keeping order in Bleeding Kansas], Smith burned these trains and the next day surprised and destroyed a third on the Big Sandy [i.e., Simpson’s Hollow].

All told the flames lit by Smith and his few dozen men consumed seventy-two wagons containing 300,000 pounds of food, principally flour and bacon—enough provisions to feed the troops for several months.”

Norman F. Furniss, The Mormon Conflict, 1850-1859, p. 109

Note the timing: October. Just the year before, Mormon handcart emigrants had suffered devastating losses in late October due to low provisions and bad weather. By burning the Army’s supplies, the Mormons knew the Army would be helpless until the spring when new supplies could get through. I think it’s a further measure of intelligent planning that they left some provisions for the troops, thereby reducing them to hardship, but not starvation.

[As an aside, there is a fascinating article which talks about a mid-winter crossing of the Rockies to obtain more supplies, which you can read online here.]

The little army marched around for a while before finally making it to Fort Bridger (which the Mormons had burnt down) to hunker down for the winter. In the meantime, Buchanan sent a peace envoy to try to find a simpler way to end the debacle.

The second result was a fatal blow to Russell, Majors & Waddell, the eventual owners of the Pony Express. At the time of the start of the Mormon Conflict, RM&W had a monopoly on supplying the US Army west of the Missouri. When Buchanan decided to sent troops to Utah in June, 1857, it was really too late in the season to send supplies: all of RM&W’s wagons and animals were already on the road. On the strength of a handshake, Russell agreed to undertake the cost and effort of freighting the Army’s materials for the occupation of Utah. So the provisions the Mormon’s burned were really Russell, Majors & Waddell’s, provisions and equipment. Because of the nature of the deal—a handshake— and the public perception of the Mormon Conflict as being no benefit to anyone but firms like RM&W that profited financially, Congress never fully compensated RM&W for its losses. This was financially crippling, and led Russell to embark an ever more risky strategies for obtaining credit. In that sense, the Pony Express was just another in a long line of financially poor business endeavors entered into by Russell to which his hapless partners ultimately became embroiled, and which bankrupt the firm, once the largest freighting operation in the west.

All due to a conflict that should never have taken place at all:

Whatever the explanation given after the event, the [Buchanan] Administration had unquestionably come to the conclusion in May 1857 that Utah’s defiance of the United States demanded stern measures. . . .

In assessing the factors that led to the ordering of armed forces to Utah, one is well advised to observe the part played by ignorance and misinformation. . . .

The view of Utah’s population in the East during 1857 was of a people oppressed by religious tyranny and kept in submission only by some terroristic arm of the Church. . . . The Saint, these non-Mormons falsely reasoned, would . . . welcome [the army] with open arms . . .

It would not have been difficult for Buchanan to inform himself of the situation in Utah. . . . [but] he had not even inquired into the facts before angrily seeking to punish the people of Utah. As a result he later found himself in the embarrassing position of sending the army in 1857 and a peace commission in 1858, instead of performing these actions in a reverse order.

Norman F. Furniss, The Mormon Conflict, 1850-1859, p. 62-60

So, yeah, Simpson’s Hollow. That was a fun stop.

A while later I came to Seedskadee National Wildlife refuge, which borders the Green River. There is not much to say here, as there was not much for me there except a postage-stamp sized spot of shade to rest in while I ate a quick lunch. The Green River runs throughout the literature from the first trappers on past the emigration. Mormons and mountain men fought over the right to operate ferries on it for the emigrants; the Green is the chief tributary of the Colorado River, and is the river Major Powell started his expedition on, the one that “discovered” the Grand Canyon in 1869. Crossing the Green was always a major undertaking, so it ended up in a lot of emigrant journals.

Whether they crossed the Green River Basin by the Sublette Cutoff or the trail to Fort Bridger, the Green River—several hundred feet wide and dangerously swift—lay as a barrier across the emigrants’ path. The Green would be the last large river that California-bound emigrants would have to cross. (Those headed for Oregon would still have to contend with crossing the Snake River.) The challenge of crossing the Green varied with the time of year and the annual snowpack in the Wind River Range. Emigrants arriving at the river in August, after much of the winter snow had melted, sometimes found it low enough to ford. Most arrived earlier, though, in late June or early July, and saw it as Margaret Frink did—running “high, deep, swift, blue, and cold as ice.” At such high water, a ferry was the only safe way to cross. By 1847 several ferrying operations, run by mountain men or Mormons from Salt Lake City, lay scattered up and down the Green River at the common crossing points. Emigrants forked over tolls ranging from $3 to $16 per wagon (roughly $60 to $320 in today’s dollars), depending on demand and river level.

Keith Heyer Meldahl, Hard Road West, p. 145

Not long after I left the Seedskadee, I turned onto the dirt roads that comprised the second half of the day’s ride. The start was not promising; a punishing climb up a loose-rock hill. The road improved further on and I was able to make decent time. But again, the area was as bleak to me as the desert of South Pass the day before.

Crossing the Green River Basin redefines monotony. The plains roll on endlessly, blanketed by the same wearisome mantle of sagebrush and greasewood. Outside of the river bottoms and the few towns, there is not a tree in sight. Scabby buttes, eroded from the stacked limestone and shale layers of an ancient lakebed, pop up here and there across the plains. The landscape is riven with ravines, most of them bone-dry in summer. The scenery has hardly changed since emigrant days.

Keith Heyer Meldahl, Hard Road West, p. 142

The brief passage describes better than I can the dreariness of the ride. Which is not to say it was bad. So long as my bike rolled along and the wind didn’t stand in my way, I was happy to ride through the desert. At points along the route, the road would be severed by a dry wash that had swept through during rain maybe in this season or maybe ten years ago, leaving two- to three-foot drops three- to four-feet wide. There were side trails to get around the chasms, and so as long as I paid attention, they weren’t too big a hindrance.

The net result is that I covered the 54 miles in about six hours. I arrived at two in the afternoon and had no idea what to do with myself. The wind was building; clouds were starting to pile up. I was supposed to meet Jessica, the caterer, though I didn’t know how or when. I found the town’s convenience store and figured I’d start with some replenishing liquids. The store was large, the selection small. I bought some kind of electrolyte and a Frappuccino and begged Annie, the woman working there, to let me drink them inside.

She and I talked while I drank and she worked on a diamond tile beadwork landscape. I told her I was supposed to meet the caterer (“Tell Jessica Annie says Hi”) and that I wasn’t sure where I was going to camp. Jessica had spoken to the mayor, who told her camping in the park was fine. But the town was having its July 4th celebration that night, so the park wasn’t a viable option. Granger sits at the junction of Black’s Fork and Ham’s Fork Rivers. Annie suggested sleeping by Black’s Fork, just a hundred feet south of the store. (“Go down by the bridge and you’ll see a road along the river,” Annie said. “You can set up your tent down there. There’s a caboose down there, too, if you want a roof. If it’s locked, the combination is . . .”)

Nothing about sleeping in a tent under a bridge—or in a dilapidated caboose—appealed to me. I was prepared to put that exploratory expedition off as long as possible.

Granger is an interesting town. It’s streets are are gravel, giving it a rough appearance. I learned that they were paved, but when the city contracted to have the water lines redone a few years back, the bid failed to include repaving, and they’ve been gravel ever since. Mining is big in the area, and trains, so there are periods of increased transient worker populations. The town also sits at the crossroads of the emigrant trails and the Overland Stage trail (something I haven’t really discussed in these pages). The main line of the transcontinental railroad runs through here (which I can attest still carries a lot of daily train traffic), and it was on the original Lincoln Highway. In 1834, it was the site of a mountain man rendezvous. A lot of history for a town of fewer than 200.

Once rehydrated, I emailed Jessica. She replied a short while later, saying she was at the restaurant (Antelope Crossing Pub), which was about a hundred yards up the street (opposite direction from the bridge). I could come by anytime.

So I rode up, stopping along the way to take pictures of the Granger Stagecoach Station, a remarkably in tact building from the 1850s that stands in a lot that appears not to have been cleaned, maintained, nor improved since, well, 1851. Jessica was on the front deck of the Pub, standing at a grill. The pub itself has been closed for some time, partially due to Covid, I think. In the interim, Jessica has set up a successful business largely catering to the mining executives who seem to spend a lot of time in the area.

[Fun fact: one of the products mined near Granger is trona, which is also mined near Death Valley. Southern Pacific dumped a trainload of Trona on San Bernardino when one of its train’s brakes failed and ran off the tracks, also igniting a pipeline. I worked on cases coming out of that incident back in my bad old corporate law days, and spent a lot of time driving between downtown LA and San Bernardino trying to save Southern Pacific from having to pay punitive damages. I can’t hear the word “trona” without recalling that period of my life.]

Jessica was grilling vegetables, she explained, for the vegetable lasagne she was going to cook for me. Now, picture that: out here in the wilds of the Green River Basin in western Wyoming, where a grilled cheese sandwich is the closest thing there is to a vegetarian dish, a women is grilling fresh vegetables for the dinner she has decided to make for me. Does it get any better than that?

Well, it does. After she was done grilling we went into the pub. She said she had nowhere to be that afternoon, and that I was welcome to hang out if I wanted. Outside was heat, wind, and possibly rain. Where else would I go? It was bad enough I’d have to go out eventually and set up a tent by the river. I was in no hurry to leave, so I followed her inside.

The pub was cluttered, which is not to say dirty. The main area is currently being used as storage space for myriad containers, etc., because everything Jessica provides to her clients has to be packaged separately to comply with Covid protocol. She invited me to sit in one of two recliners by the bar counter. I did, and she talked, and in the dim light of the cool room, I became sleepy. So told me to feel free to recline and take a nap. She didn’t have to tell my twice. I was out.

When I woke sometime later, Jessica was still behind the counter preparing food. I was suddenly struck with a weird kind of panic. It was a little after three in the afternoon. What was I going to do the rest of the day? I wondered if I had enough time to dash down to Little America, on US 80, and get a motel room. But while all this was going through my head, Jessica and I were talking and it was a very relaxed, pleasant sort of conversation about nothing in particular. Not empty talk, not in the least annoying. There are times I can’t talk on the phone without doing something else, walking at least. But here, relaxing in the lounger in the dim light and cool air, I was perfectly at ease. Again, Keith Heyer Meldahl captures the spirit of my conversation with Jessica perfectly.

After a day of pummeling by Wyoming’s biggest bully, I can vouch that nothing is more welcome than a building—shelter—even if it is a run-down gas station in a run-down town like Farson, a forlorn little hamlet marooned in the sagebrush wilderness of the Green River Basin. I sipped burnt coffee there one afternoon, hiding from the wind, while leaves, newspapers, and other flotsam flew past the windows. Was this typical? Oh yes, the attendant sighed. The windows appeared cloudy. A closer look showed that they had been etched by windborne sand. Merciless wind and winter beat up the small rural towns of Wyoming. The results are evident as potholes, peeling paint, broken roofs, leaking pipes, and plywood windows. Yards spill over with rusted cars, wrecked parts, writhing heaps of hose and pipe, and tires—many, many tires. Anything that might be useful, might a save a few dollars one day, joins the heap. But local folk brim with friendship and conversation, a pleasant upshot of life with so much open space and so few people to fill it.

Keith Heyer Meldahl, Hard Road West, p. 142

Jessica told me she loved (at least) two things: cooking for people and learning about their lives and experiences. Which explained why she was willing to cook dinner and breakfast for me when she had so much other work to do. Not that my life is all that interesting, but she couldn’t know that ahead of time. So she cooked and we talked and all in all it was a slow, pleasant afternoon spent out of the weather.

Sometime later, while the smell of cooking lasagne filled the room, she spoke with her husband, Ed. She told me he’d be there in a bit and that they’d agreed I was welcome to stay in the pub if I wanted. Another wave of relief washed over me. You have no idea how much relief. Between the wind, the heat, the mosquitoes . . . not to mentioned the possibility of being told to move by the police (if there were police in Granger).

And it was one of those things: when was the last time you sat and talked with someone for an entire afternoon? How do you carve time like that out of your life? It’s like Meldahl says, Jessica brimmed with friendship and conversation, and I was there to benefit from it. I can only hope that what little I had to offer back was worth her time.

Ed came in while we were eating—that is, while Jessica nibbled and I shoveled down two entire dinners. He was just as friendly, but he had his prickly side too. Where Jessica might drop a hint as to her politics (“Democrats don’t like mining”), Ed seemed to want to provoke a little debate (“Are you going to vote for your Governor again?”). I sidestepped any discussion of politics. I’m pretty sure my and Lisa’s votes negated Jessica and Ed’s votes at every federal election, and vice-versa of course, so talking politics couldn’t have led anywhere worth going. But our different opinions didn’t stand in the way of getting along here. In fact, Ed offered, practically insisted, that he put me and my gear in his truck so he could gladly get me safely to Salt Lake City, no trouble at all. It was as if now that I was in his place, I was his responsibility, and he’d do whatever he needed to keep me safe, even if I did vote for Biden.

Jessica asked, and I told her I wanted to be on the road by nine in the morning, so she said she’d come by around seven-thirty to make a veggie breakfast burrito for me. Ed set up the coffee maker so all I’d have to do was push a button in the morning. Around sundown they left to go home. I set myself up with a sleeping bag in the lounger and had a pleasant night’s sleep in that little pub, a building I think I stayed inside of the better part of 18 hours straight.

I can’t hear the word “Trona” without remembering going through there in the dead of night, crewing for a DBC team riding the Furnace Creek 508. Knew for certain I didn’t need to revisit. Your tales are must-reading, Scott. The quotes from your research combined with your observations and interpretations and feelings about it all brings your ride into my head and heart. Roll on. —babz

Of course! That’s where they mine it from. Your association sounds much more pleasant than mine, though I’m sure crewing was no picnic. I’m so happy you followed along on this journey. Thank you!

Lovely. The kindness of strangers… in Granger. Feels like a song could be made from that.

-Kathy

I’ve wondered about the political divide and how you handle that. Thanks for explaining it.

Sounds like a sweet experience.

It was. Again, something I never could have planned and never would have anticipated.

So much sweeter when its not expected.

-Valerie

True!