Still in Evanston, WY, before my final push over the Wasatch Mountains to Salt Lake City. The ride I describe below was from Rock Creek Hollow to Farson and, well, you’ll see . . .

=============

July 2, 2021

Rock Creek Hollow, WY to Farson, WY

53.9 miles/1,240 ft

mid-80s/winds 15-25+, in my face

https://ridewithgps.com/trips/70434138

It sounds like I’m making this up, but I went from the best ride of the ride yesterday to the hardest and least fun today. As my friend Anthony would say, if it were a fight they would have called it. And I would have been the loser.

Things started off on a bad foot when I rolled into soft sand on a stupidly steep climb right out of Rock Creek Hollow not 100 yards into the day’s ride. I had to walk to the top of the grade. Not the end of the world, but in retrospect, a harbinger of bad times ahead.

Once out of the hollow I was into the wind. This was not a gentle morning breeze, nor a light stirring, only to freshen later in the day. It was already 15 mph at 8 am and I couldn’t see any reason why it would drop any lower. And, no it didn’t, and yes, it was a headwind.

I was riding across a desolate high-desert plain. The steppes of central Wyoming. The kind of area where no plant is able to grow taller than six or eight inches. Bonsai sagebrush as far as the eye could see. Nothing for miles except an occasional rabbit or antelope. Now, some people appreciate this kind of environment, and I applaud them. I also realize that calling a desert “empty” is to betray an ignorance of the abundance of life there. So I guess I would say “empty” as in no landmarks, nothing to entertain the eye. Just a lot of sand and rock and sagebrush and rolling terrain to drop into and climb back out of. And that was just the first mile.

I crossed a dirt road and had to make a decision: the Bikepacking Route turned left to go around a piece of private property. I had written to the owner and received permission to cross his property. Should I stick with Jan’s route, or be the cool guy who gets to ride the special route? What do you think I did?

Dumbest decision of the entire ride.

Not soon after I blew off Jan’s route, I came to a creek. And what do you know? This is western Wyoming. Bridges? Who needs bridges? I would have to ford it or turn around. I’d forded three creeks the day before. I was a pro now. And this crossing wasn’t very wide and didn’t look too deep. So I moved ahead.

As I got closer, I noticed the area I was in was very narrow, maybe 30 yards wide, and short, maybe 150 yards long. It was fenced in on both sides, gated front and back, and filled with about two dozen cows who were milling about, mooing their displeasure at my presence. Now, here’s the thing about cattle and water and small spaces. Water from the creek seems into the surrounding ground, saturating it. Cows are heavy, and they go to the water to drink or to cross the stream. The heavy cow steps on the wet land. The end result is a landscape of three-foot tall mounds, like bales of hay that have grown over with grass, a maze of cow tracks weaving among them. Plus a lot of cow poop. Everywhere.

While I might be able to negotiate the labyrinth of cow-defiled paths among the mounds if I had only my bike, it was impossible with a trailer. So I unhooked the trailer, carried my bike to the last firm piece of ground before the creek, then went back and carried my (heavy) trailer and hooked it back up. In the wind, of course, because it was windy even here, because Wyoming=Wind. I got everything lined up, then pedaled through the creek without getting anything wet, other than my wheels. Cool. Not too muddy. Not so bad.

Once across and on solid enough ground I unhooked the trailer again and carried the bike and trailer past the poop-besmirched maze of cow-mounds on the far bank and hooked it all up again . . . Only to ride twenty feet and find that there was another creek to cross. I could not see it because this was rising ground: the undulation of the land hiding what lay at the bottom of the rises. Where I expected to find a depression, I found instead another unbridged creek.

Now, a lesser man would have turned around at this point and, tail between his legs, so to speak, retreat to the bikepacking route as mapped. But this creek didn’t look too bad either, and I didn’t want to carry the trailer back over what I had just worked so hard to get across.

Same drill. Sweating now from the effort. But I got across, hooked up, and rolled uphill toward where the cows had migrated, only to find that there was a third creek.

Cussing ensued. It got worse when I saw this was not so much a creek crossing as more of a cow wallow, and one that this little herd cows had just crossed to get away from me, leaving who knows what behind. The mud was squishy a good distance back from the bank, so I couldn’t approach it with the bike as I would only get mired before I got to the water, and the water was too deep to cross on the bike. I would soak my shoes and the trailer, with all my gear, food, etc.

I walked back and forth across that thirty-yard space for fifteen minutes trying to find another way across. There were two fences: barbed wire and what looked like electric fence. I’d heard that once cattle touch an electric fence, you can turn it off because they’ll respect it. I tested the top wire. ZZZTTT! That one’s live. And a lot more of a shock than I’d expected. I walked the length of the wallow again and came back to the same place. Seems I’d read that only one wire was live, so I wonder if this bottom—ZZZTTT! Nope, it’s live. Ouch!

I finally concluded that the only way to cross was to take my shoes off and carry everything through the wallow.

You have to realize, at this point I am only about a third of a mile from the Pony Express Backpacking Trail. Yes, I’d have had to carry my gear and re-cross two creeks. But I could be back there and on my way in twenty minutes or so. Or, I could move on, get across this wallow, and keep going where so few riders will be privileged enough to ride. And I can’t believe it myself, but yes, I took my shoes and socks off (noting the amount of poop on the soles of my shoes), and carried my gear in two trips across this disgusting little cow wallow, sinking more than ankle deep in the mud, knee deep in muddy water, and then through yet another poopy maze of cow tracks on the other side.

By the time I dried my shoes and hooked up and got ready to go, the cattle were all huddled at the gate at the top of the hill. The gate I needed to get through. The rancher told me to make sure to close all gates I opened, and with the cows there, I had this image of them charging through the gate once I opened it. So I rode my bike directly at them, yelling at them to get out of the way the entire time. To my great relief, they did. All in all I probably spent forty-five minutes working through this short fenced area, a huge waste of time so early in a long day’s ride.

From there to Burnt Ranch was a straightforward, if strenuous, ride. Hills and valleys, soft sand and sharp rocks, and all the time wind, sometimes steady, sometimes gusting. But this was the Pony Express Trail, or so the concrete posts told me. The Oregon, California, and Mormon Pioneer Trails. So in moments when I was thinking how difficult this was on a bike, I imagined how much more difficult it would have been walking while whacking oxen, or lugging a handcart in the bitter cold with the remainder of your worldly possessions. I also thought about being the Pony rider on this stretch, and what a dreary route this would be to have as your back-and-forth run. Especially in winter.

On that note, I just have to add that many people who write about the Pony Express themselves express a certain sadness, a poignancy at its passing. They talk about the telegraph “killing” the Pony. All I have to say to that is good riddance. What an incredible waste of so many lives. The messages the Pony carried were essentially telegrams, notes on tissue paper to save weight, and sent mostly between businesses because the average person could not afford its rates. The telegraph that replaced the Pony Express sent messages in minutes that took ten days, required scores of riders and station keepers, hundreds of horses, mountains of feed, water that sometimes had to be carted to remote stations in the desert . . . It was an enterprise that bled money from day one and did not accomplish any of the goals normally attributed to it. On some level, I have to wonder if the people who mark its passing with regret are, like me, the same people who get angry when their Amazon Prime purchase does not arrive in the specified two days. The progress of mail has always been toward faster, more reliable delivery. The telegraph beat the Pony Express as readily as Amazon Prime beats standard mail, and who doesn’t prefer the faster service? The Pony Express of popular culture is a romantic fantasy, a fiction, and like all such fictions only looks beautiful from a safe distance. I challenge anyone who bemoans its passing to put their butt in a bike seat and ride the route from Rock Creek Hollow over South Pass to Farson, Wyoming, to endure the mosquitoes and the wind and the utter desolation, and then tell me they still think the death of the Pony was a loss in any sense.

Eventually, I descended off the plain toward the Sweetwater River and the last (ninth) crossing at Burnt Ranch. The river was welcome sight, its verdant strip of abundant life running like a green scar through the khaki hills.

The ninth and final crossing of the Sweetwater River was variously called Gilbert’s Station, Upper Sweetwater Station and South Pass Station. In 1849, travelers who had reached this point found traders, including Jim Bridger, ready to sell them horses, oxen, bacon and buffalo robes.

https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/ninth-and-last-crossing-sweetwater

And here is where the next part of my adventure began. The map I was following told me to go northwest to find a bridge over the Sweetwater. I rode in that direction and found a canal (unmarked on the map) between me and the alleged bridge. Not being in the mood for more water crossings that day, I rode around the area looking for a trace of a trail, anything that might lead to the bridge the map told me was there. Not having any luck, I reviewed the email the rancher had sent. His note mentioned a bridge to the south, not the north, so I went in that direction. I found a bridge and crossed it. But I still had to get to the northwest to rejoin my trail. I rode another quarter mile to where the map showed a bridge crossing a different creek. If I could get across that creek, I could rejoin my trail.

But at the place the map showed a crossing, there was no bridge, and the water here was far too wide and deep to carry a bike and trailer across. So I rode back to the main ranch area and searched for the missing bridge. I unhooked the trailer and scouted every likely approach. I crossed boggy land, small rivulets. Nearly everywhere the earth seemed to want to swallow my bike. The only good result of all this effort was that I stumbled across the Burnt Ranch Station marker, which I had missed earlier. That was something anyway.

I tried calling the rancher. No cell service.

After twenty minutes or so, I gave up and in a pig-headed sort of way decided I’d reattach the trailer and just stick to the mapped route and cross whatever obstacles I came across.

I didn’t have to wait long. The first obstacle was that canal crossing. I rode around it, picked up what might be a trail, and soon came to a creek that fed into the canal. The map said a bridge lay on the other side, so I went about crossing the creek. It was maybe too deep to ride through, but at least was clean and clear. Just to be on the safe side, I took off my shoes and socks and carried everything across. No problem. I dried my feet and put shoes and socks back on, reattached the trailer, and headed off according to the map. Water everywhere. Saturated ground. I could plow my way through, and did, until I came to a dead end: a fence with no gate. I stopped my bike and put my foot down and felt it sink into the saturated grass. If this were evening, I would probably still be there, a husk of flesh with all the blood sucked out by mosquitoes. The one thing I have the wind to thank for is being strong enough to keep those blood suckers at bay.

I found a reasonably dry place to rest and surveyed the area for five minutes, thinking the entire time of how much time I had already lost that morning, of how much further I had yet to go. Finally, I came to the conclusion that this was dumb; that there was no way forward; that I would have to recross the creek; that the only bridge must be that one to the south; and that if I could not rejoin my planned route, the bridge road had to lead somewhere. Worst case was I would end up miles off course, but eventually I would find my way back to the Pony Express route somewhere in Wyoming. I couldn’t just sit at the ranch all day, and I sure wasn’t going to ride all the way back and recross three streams just to get to Jan’s trail and start the day over.

I stopped at the creek edge and reassessed its depth. I had left my camp at Rock Creek Hollow more than two hours before and had covered less than ten miles; I had another forty-five miles to go; daylight was burning, and I was sure the wind was building because, you know, Wyoming = Wind. I decided to save a few minutes and chance it by riding across the stream, and proceeded to soak my shoes and socks and everything in the trailer that wasn’t protected inside my Patagonia Black Hole bag.

But no time to worry about that now. I kept riding. I recrossed the bridge to the south and stopped at the supposed crossing which wasn’t before shaking my head and moving on . . . Only to discover that fifty feet further on there was an unmarked crossing. A passage over a culvert, dry as toast. I could take that, ride north up a steep hill, and in a half-mile rejoin my route. (Looking at the route weeks later, I realized that this crossing was where my detour through Burnt Ranch rejoined the Bikepacking Route detour.)

Man, I felt dumb. If only I had taken the time to notice that earlier. By the time I rejoined my route I had spent an hour wandering around Burnt Ranch. If you take a look at the map linked above you can see my wandering—and the GPS is attached to the trailer, so it didn’t record the scouting I did with just the bike.

Once back on the plain from the river bottom, I was back to the northwest slog into the northwest wind. Once again, nothing to do but my head down and do it. I got tired of wet feet and changed into my lightweight off-the-bike shoes. The softer soles transferred more stress into my feet, making pedaling harder, but at least my feet were dry.

On and on I went. To my right was the southern end of the Wind River Mountains, the north gate of South Pass. To my left were buttes, which I knew had names but which names I didn’t recall. As I neared South Pass, there were occasional signs placed by Wyoming marking landmarks like the Twin Mounds, piles of dirt the emigrants passed between. In my deteriorating energy and mood, I found none of it very impressive.

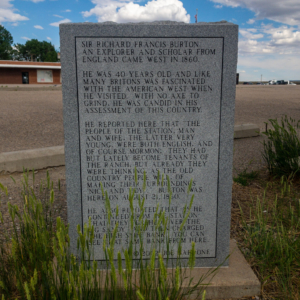

Until I reached South Pass. This was a spot that, in spite of everything that had happened that morning, I stopped to savor. The 7,500’ high pass through the Rockies, the wagon road that enabled western emigration. The marker placed there by Ezra Meeker in 1906, himself an Oregon Trail guide from the mid-1800s. It was one of the few places on the trail that to me felt like an accomplishment. I took the time to enjoy a snack and the milestone.

Here’s the kicker: for emigrants, this only marked the half-way point on their trip to the Pacific Coast. Can you even imagine?

The actual pass is nothing spectacular. Emigrants remark on how they didn’t even know they’d crossed it until they reached Pacific Springs a few miles further and noticed the river flowing west instead of east. It is in that sense, the notion of an eventless event like crossing South Pass, that I initially named this post “Expect Nothing.” I’d meant it as I should expect nothing special about this spot. But after the ride I’d had that morning, I now saw the phrase more as a suggestion to be open to whatever challenges might come my way. That is, not to have a preconceived notion of things are, or how they should be, because it becomes too easy to use that notion to restrict myself and my possible options to these predefined ideas. Like trying to ride northwest through boggy land, for instance, because a line on an electronic map says there is a bridge in that direction and no canal in between. It is easy to stand on the edge of that unmapped canal and not see that mapped bridge and think it has to be there. It’s just as easy to focus so closely on a submerged creek crossing that you fail to see the dry crossing not fifty feet away. In some ways, that is, it’s easier for me not to see what I am looking at than to realize perception and reality at this point are misaligned, that I need to stop looking at the screen and start focusing on the world around me to find my way out of the morass.

(This is also truer to the meaning of the phrase as it was used in the movie I stole it from, The Yakuza, with the great Takakura Ken and Robert Mitchum.)

So anyway, here we are at South Pass, crossing the barren Wyoming steppe in the face of a howling wind, with another four or so hours to ride. Incredibly, the west side of the pass, the weather side, was even less hospitable than the east. Barren, exposed rock and washed out road. It had some downhill, but was in bad enough condition I still had to ride slowly. Pacific Springs, like the Sweetwater on the other side, cut a lush green swath through the desolation, but the road stayed up higher and more exposed.

After some more miles of riding through this rough country and into the harsh wind, I reached a highway. And yes, I know I am a hypocrite, but man was I relieved to see that highway. Miles and miles of smooth pavement. Jan’s route follows the highway for some miles before turning off. On her map, she notes that after the turnoff the trail has areas of deep sand and to expect slow going. I had to wonder, wasn’t that deep sand I had just ridden? Didn’t I just struggle through miles of slow-going trail? If so, and she didn’t mark that section, how much worse would the next section be? The sky was filling with clouds, threatening rain. The wind still whipped around me. There was no way I was going to add another hour or two to this day just to be authentic. Honestly? I don’t think I had it in me. I was going to stick to the highway, rushing trucks whizzing by me and all, until I reached Farson. Decision made, I rolled slowly on.

The place where Jan’s route turned off has a memorial for the Parting of the Ways. This was where the California and the Oregon emigrants separated. Families who may have traveled together since the Missouri River, or from even further east, would leave each other here. They were headed to different destinations, and this was likely the last they’d ever see of each other.

I read somewhere that during the emigration years at the Parting of the Ways there was a sign which said “Oregon,” with an arrow pointing right, and “California,” with an arrow pointing left. It was said that those who could read turned right and that the rest turned left. An anecdote written by an Oregonian, no doubt.

My notes tell me that this point is actually called False Parting of the Ways because the real spot was further ahead. But that was on the deep sandy road, and I just didn’t need to see the actual parting that badly.

From here to Farson I engaged in a three-hour grudge match with the wind. It blew at me from three sides, left, right, and center forward, but never aft. A shoving, bullying wind, so unlike the kinder winds of that breezy Nebraska day I rode to Gothenburg. It was like a devil, teasing me, trying, and at times succeeding, in stopping me in my path. During particularly strong gusts I said aloud, “Thank you for that.” Other times I substituted a different word for “thank.”

To say it was an exhausting three hours is an understatement. I kept wishing someone would pull over and offer me a ride, kept considering stopping and sticking out my thumb. There are certainly enough pickup trucks in Wyoming; any one could easily haul me and my gear. That is not to say this was necessarily the strongest wind I had ridden in, or the worst conditions. It was more that the frustrations of the morning—crossing those creeks, getting lost at Burnt Ranch, wasting so much time—had burned up so much of the morning energy, which usually propels me far into the day’s ride, that I had so little reserve left.

The road itself didn’t help. Another thirty-mile stretch where there isn’t a hundred feet of level surface at a time. The only grace, was whereas east Kansas roads have two or three hills per mile, this had hills that rolled for two or three miles. Some were still stepper than I would wish—well, any hill at this stage was steeper than I would wish—but there was nothing too steep here. Just annoyingly persistent in its rolliness.

And the country . . . More desolation. This was the Red Desert the rancher had warned me about way back at breakfast in Casper. The emptiness of it. Even Irene Paden found it bleak:

Well within our view as we stood on the mountain it strikes the sage flat, passes the small rocky trail landmark called Haystack Butte and goes on and on interminably through a dreary waste.

Irene D. Paden, The Wake of the Prairie Schooner, p. 237

This area abuts the Green River Basin, which Keith Heyer Meldahl describes in a fashion equally applicable here:

Only the wind seems happy in the Green River Basin. It shrieks with glee across the plains, sweeping up wraithlike clouds of grit. “It has been windy, and there is nothing but sand—sand all around us, which is drifting constantly, filling our eyes and ears, as well as the frying pan,” A. J. McCall groused, adding, “It is not strange that it affects the temper of the men—marring all good fellowship.”

Keith Heyer Meldahl, Hard Road West, p. 142

At length, I made it to the Eden Valley, where Farson sits. The road dropped off the plains down a gentle decline, and almost as if brought to heel, the wind calmed and blew steadily out of the northwest. It was still strong, still more in front of than behind me. But it was a tamed wind, a civilized wind that kept in its lane. I could work with that for the last ten miles.

Farson is yet another tiny high-desert town, a crossroads of two highways on the Big Sandy River. Keith had told me the day before that the Mercantile in Farson sold ice cream, and that he was pretty sure they had a camping area in front of the store. I didn’t know if either piece of information was true, or if so, which would make me more happy.

At this point I’d been on the bike for eight hours. Not an incredibly long day by some standards, but they were not a easy-going eight hours. I was beat. I sat on the Mercantile’s outside deck (under a sign that said “Home of the Big Scoop”) and drank electrolytes and had a snack and generally stabilized myself to the point where I could walk a straight line and speak coherently, two things I had not needed to do for the previous twenty-four hours. I went inside, and yes, there was ice cream. They offered five sizes, from Baby Scoop to Four Scoops. I asked the woman behind the counter if the four-scoop portion was ridiculous. She nodded and smiled and said yes. So I ordered one with chocolate and vanilla ice cream. While she scooped I went to get a Gatorade to slug down for coolness and more electrolytes. The cup she handed me was huge, and there was as much ice cream on top of the cup as inside it. Everyone in the shop who saw it pointed or laughed. It was ridiculously large, a quart of ice cream at least. By far the most I’ve ever seen served.

As I was paying I asked about camping. The clerk told me there was primitive camping for free behind the store. Keith was right on both counts. I felt a huge wave of relief. No matter how primitive the camping was, it meant no more riding that day. And I had a boatload of ice cream to eat in the meantime. Life had turned from bleak to plush in the space of fifteen minutes. Farson didn’t become my new favorite town, but it was a lifesaver that day.

I went outside to eat, but found the sun too hot. I went back inside to a small air conditioned dining room and got the shivers but worked my way through the ice cream just the same. Later I found a patch of grass to set up my tent, then used the dining room and rest rooms of the Mercantile for an impromptu office and place to give myself a sponge bath, respectively. while changing my shirt in the tent, I found a tick trying to embed itself in my stomach. I got rid of it, but had a frantic time making sure there weren’t anymore. Ugh.

It had been a very long, trying day, and I had another one of equal distance, about 54 miles, the next. I ended up going to sleep without dinner, if you don’t count the ice cream. I wasn’t hungry anyway, and I knew that once I made it to Granger there would be a vegetarian meal specially prepared for me. I went to sleep hoping for an easier ride the next day, and if it wasn’t too much ask, anything but headwinds.

Wow that’s nuts. I can’t believe you read that about the trail and still found the attraction to actually do it. I’ve been through cattle bogs before hiking Switzerland and they are a mess, and you did it barefoot oh geeze! Cheers to getting through today, definitely deserved every bit of that ice cream 🙂 Hoping you get the chance to hose down somewhere.

I had an encounter with cows that were following us in a muddy field in Scotland, and my 8 year old daughter freaked, sure they were bulls. “They don’t have utters! They don’t have utters!” They were heifers. In the panic, the mud sucked one of my shoes off, and I ended up taking my trousers off outside my aunt’s house and hosing them. Which brings me to a question: when you went into buy ice cream, didn’t you smell like manure? Did the proprietor put the ice cream on the counter for you and back away?

I wiped the soles of my shoes off on the wet grass before I put them back on. As for smell, I have no idea what I smelled like, but I didn’t see anyone wrinkle their nose or back away. I wear anti-microbial shirts, but also had on sunblock and insect repellant. Now that I think about it, maybe I had an odor-sealing layer of sand adhered to the lotions.

Oh my gosh- how do you stay motivated after such a grueling, exhausting day? Ice cream ? I have a vision of you riding and yelling at cows.

-brenda

Ice cream helped quite a bit. Yelling at cows was kind of fun, too, though their size still makes me nervous.

Very Funny…CA or OR! Who would of thought a significant life choice would boil down to a random fork in the road. Just think if ol’ Grandpa Ikemoto had randomly decided on one boat pier or another. I thank him everyday for boarding the one to CA but wouldn’t complain if he decided to call it in Hawaii.

Suffering on the bike is like parenting. You endure far more than you signed up for and then simply forget how incredibly hard & demanding it was at the first sign of comfort/good night’s sleep. One trick to make the next day legs a little less rusty is to do Legs Up the Wall each night (if at a motel). Lie on your back w/ your rear end as close to a wall as possible and keep your legs at a 90 degree angle, up the wall for 5-10 min. Helps circulation. There’s a few more yin-style (low effort/always laying on the floor) yoga poses like holding pigeon for 3-5 min each side and any iteration of a forward fold which also help counter being hunched over the bars all day.

What a challenging day. The beast in you got you through it!! Your ice cream award was the best dinner ever! Thumbs crossed for a better day tomorrow

Not going to lie / I smiled while reading about your cattle encounter – lol :). *Carla

I probably deserved that.

You’ve got your book jacket quote: “I challenge anyone who bemoans its passing to put their butt in a bike seat and ride the route from Rock Creek Hollow over South Pass to Farson, Wyoming, to endure the mosquitoes and the wind and the utter desolation, and then tell me they think the death of the Pony was a loss in any sense.”

Good point! Now if I could just find an agent . . .

You’re reminding me of Winston Churchill’s explanation of the absence of a revolutionary tradition in the USA—low quality of the toilet paper, nothing suitable for the recording of manifestos.

I like that.

Now you can add cattle driver to your resume! And I notice that your conversations with the wind resemble your conversations with your computer. Glad but not surprised that you made it with your spirit and humor intact.

I think you can thank the mountain of ice cream for that.

brutal

Wow Scott, I don’t know how you do it but you conquer all that is thrown your way, and it seems like a whole lot. A lesser man would have called an uber by now. And, powered by ice cream as well. Kudos to you Laughing Dog.

Stu

Stubbornness, Stu. Blind determination. And the ability to make the worse choice (going forward) sound like the best (when going back would have been the smart move).