Taking the day off today, cooling my heels in Sidney, NE while the sun heats the world outside. In my original plan, I would have ridden to Bridgeport today and taken a break there: that’s the final town on the second leg of this trip. But as a practical matter, it really doesn’t matter where I take a break.

When I leave Sidney, I will make what in emigrant times was a dry passage to Bridgeport, where the emigrants who came this way (via the Upper California Crossing by Julesburg) rejoined those who took the Lower California Crossing (via Brule, California Hill, and Ash Hollow). They all then moved together along the south bank of the North Platte toward Fort Laramie, the first settlement since Fort Kearny.

I had breakfast at Grandma Jo’s this morning, which was atmospheric, but not particularly tasty. There was a table of old guys sitting around drinking coffee and talking. It seems in every small town with a diner there is a group of old guys who sit around a table and drink coffee and talk all morning. Sometimes they have names and table plaques, the “Do-Nothing Club” and the “Procrastinators’ Club” are two that come to mind. These gentlemen didn’t have a plaque, but they were definitely a fixture.

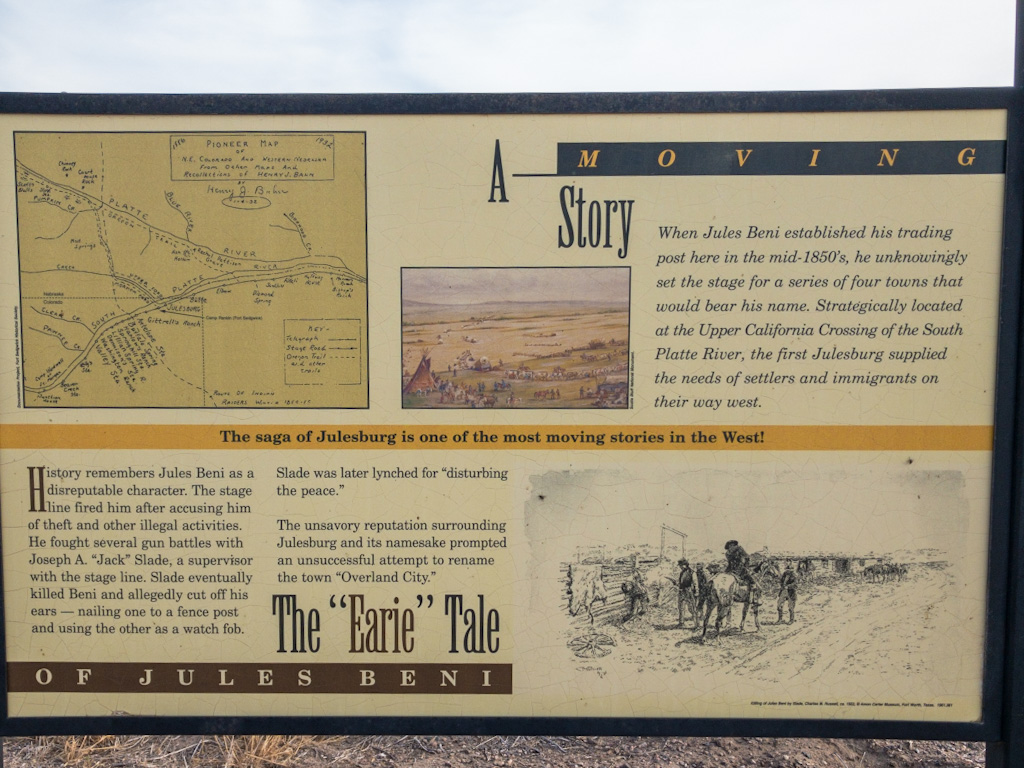

Wandering around the town, I came across some interpretive signage on the history of Sidney. It seems “Sinful Sidney” had something of a Wild West side to it in the 1870s and 80s. Speaking of the Wild West, I promised a story about Jules Beni and Jack Slade.

==================

Jules had set up Julesburg in a strategic transportation spot. When stagecoaches started running from the Missouri to Denver and to Salt Lake City, the lines needed stage stops. It made sense to use whatever existing facilities and personnel they could to save expenses. So Jules became a station master. I could go into the details of which stage and mail lines existed, where they went, how long they lasted, who owned them, when ownership changed hands, how routes were altered, the intricacies of US postal subsidies, etc., all research I have notes on . . . But rather than complicate things, I’ll leave all of that out for now. The important thing is that Jules was the station master in Julesburg.

And Jules had this game he liked to play with the stagecoach companies. One of the main functions of a station was to keep and upkeep the animals that hauled the coaches (usually mules) and other livestock. Jules was friends with Native Americans who lived in the area, in fact was married to a woman from a local tribe. Every so often, Jules would ask his buddies to “run off” the livestock, leaving the stagecoach company in a bind because its stages could not continue with fresh livestock. He would then go to the local representative, offer to search for and negotiate the recovery of the livestock for a fee, then have his friends bring the livestock back to Julesburg. This was not an original idea—I came across it in a few other settings—but it was a lucrative side business.

Apparently, the stagecoach companies put up with this arrangement until the Pony Express came along and also contracted with Jules to be a stationmaster. The difference is that normal stock, the mules and such, were relatively inexpensive. Pony Express horses, on the other hand, were of a better stock and more valuable. Plus, the Pony Express contract called for a strict time schedule. Ten days from the Missouri River to Sacramento did not leave a lot of time for delays.

The Pony Express line superintendent, Ben Ficklin, needed someone to rein in Jules. He decided to fire Jules as station master and install someone he could trust. The trouble was, Jules had a violent reputation. So Ben Ficklin brought someone in he thought was tougher. That was Alfred “Jack” Slade. (I could go into Slade’s reputation and why Ficklin thought he was right for the job, but again, I just want to stick to the story at hand.)

So Slade went to Jules and told him he was fired. Without going back into my research to get all the details straight, sometime soon after Slade was eating in Jules’ restaurant at the station. After dinner, Jules followed Slade outside—all accounts specify that Slade was unarmed—and blasted him with a shot gun and a pistol. Somehow, Slade didn’t die immediately. As it happened, about this time a stagecoach pulled in and Ben Ficklin was on it. He had a couple of men take care of Slade while he and a couple of others took care of Jules. They did the thing you see in Westerns where they throw a rope over something high and hung him. But they stopped before he was dead because they had a dilemma: Jack Slade hadn’t died yet, so they couldn’t rightfully execute Jules. Remember, there was no law out here at this time. It was all code. And the code was they couldn’t kill Jules unless Jules actually killed Slade.

They lifted him off the ground twice more. Finally, Ficklin told Jules they’d let him live if he left town that day and never came back. Jules complied . . . For a time.

Meanwhile, Jack Slade healed up well enough to travel, then Ficklin sent him to St. Louis to get operated on, though apparently they never got all of the bullets out of him. Nevertheless, he recovered well enough to take up his position again as supervisor of the stage line in his district.

A couple of years later, Jules decided he wanted to come back. Evidently he was fairly vocal about killing Slade if Slade interfered. At length, it became clear that in a territory that had no established law, if Slade let Jules go on as he was, Slade would lose his authority over the lawless element he was hired to take care of.

Slade went to Fort Laramie and met with the post commander, explained his intentions, and was told the Army wouldn’t take any interest in the matter no matter what he did to Jules. Slade then went about hunting Jules down. And here the record gets murky.

Eventually, Jules was dead. The question is, did Slade kill him, and if so, did he torture him first? The most prevalent accounts support the torture scenario, with Jules tied to a post and Slade shooting one part of him or another, going into the bar for drink, then coming out to shoot some other part. Another version says a couple of Slade’s stagecoach employees found Jules and sent word for Slade; that Jules got wise and tried to escape; that the employees shot him, then tied him to a post to keep him from escaping; and that by the time Slade arrived, Jules was already dead.

The detail everyone agrees on is that Slade sliced Jules’s ears off and carried one around in his fob pocket for the rest of his life, which, as matter of fact, lasted only a few more years. He ended up being hung by Montana vigilantes for a particularly destructive bender. Slade was a very destructive drunk.

Over time, a number of atrocities have been attributed to Jack Slade, starting with his alleged killing of a man when still an adolescent. Like most stories about bad men from this period, most of them are fabrications.

When I started my research into the Pony Express, I had come across Slade’s name, but didn’t have any interest. I don’t really care much for the bad man thing. But I read a biography of Slade written by Dan Rottenberg, Death of a Gunfighter, which changed my perspective. Rottenberg has combed through a lot of primary and secondary research about Slade, and his book looks at each of the acts attributed to Slade over the years from all available sources at an attempt to get at the truth. When he makes a judgment call, he explains his reasoning. (For instance, he ascribes to the employee shooting of Jules rather than to the torture scenarios.) Most of all, he loves his subject and is the rare writer whose enthusiasm comes through in his writing. It is really a wonderful book.

Rottenberg’s book had grabbed my attention, and ever since, I feel like I’ve become a Jack Slade apologist. Whenever I read an account of Jules’s murder, or come across a dime-novel characterization of Slade in a movie about the west, I feel insulted and want to set the record straight. No question: Jack Slade could be bad news if you were on his bad side—or even if you were on his good side and he was drunk—but he does not seem to have been a bad man.

That’s why I was so looking forward to seeing Julesburg. I realize that the Julesburg I saw was the fourth location. I also realize that even back in the 1930s, when Irene Paten was looking for remnants of the original Julesburg, they were all gone. Of all the stories and biographies related to the Pony Express, I find Slade’s the most complex and the most interesting. It was fulfilling, somehow, to stand near a place I’d read so much about, however removed by time and circumstance. It was worth going a few miles out of my way on a day that threatened to be excessively hot, a day on which I would have been well-advised to take the shortest route to my destination. Because, really, what is the point of riding a historical route unless you feel some personal connection, however tenuous, with something about the route’s history?

You slayed this one.

Fabulous. Thank you for taking the time!

Good story! Glad you’re taking a break. Tomorrow it’s going to be 106 here !! Yuck ?

Do you have any weapons for self defense against crazy people? Safe travels- brenda

No weapons. I’m pretty sure I’d be outgunned anyway. All I’ve run into so far are good people.

Loved the Jules/Slade history. He kept his ear!

LOL!

Stay calm, cool & collected

Apparently Slade would “accidentally” pull it out of his pocket and let it fall on the table or anywhere convenient to impress the other party.

“Ears to ya” was his toasting slogan.

Ouch